By Dr. Stephen Briggs

Photos from the Berry Archives

For the last 25 years, our nation has been riding a wave of disruptive innovation. Three of the world’s wealthiest companies – Amazon, Google and Facebook – were founded, reshaping our culture. We have come to accept the value of disruption and its inevitability.

Now disruption has emerged in a more ancient form. The turmoil and uncertainty created by the COVID-19 pandemic offers an opportunity for us to realize just how much we take for granted the relative health, safety and prosperity we have enjoyed in our lifetime. While we can point to many vexing problems and injustices here in America, we still live in a time and place of unrivaled privilege.

A century ago, the Berry Schools endured an earlier pandemic directly in the wake of a devastating world war. As we come to grips with the intensity and abruptness of our current challenge, it is helpful to see this moment through the perspective of Berry history and thereby consider some time-tested yet timely lessons anew.

A gathering of Berry servicemen after World War I.

The context

In April 1914, Martha Berry journeyed to Europe. After more than a dozen years of exhausting effort on behalf of the Schools, she was, in her own words, “tired and broken down from the work.” She spent several weeks in Italy with her sister before journeying to the hot springs in Carlsbad, then a part of Austria, “to try the cure.” She was there when war broke out. “It came as a clap of thunder from a clear sky,” she wrote. Several titled Russian women, quite ill, were whisked off to the rail station on stretchers. Before long, Martha Berry was the only guest remaining at the inn out of more than 100.

There was no easy way for her to leave safely. She decided to brave a route that took her by train to Amsterdam. What should have been a 15-hour trip took six days as passengers were searched at military checkpoints and sidetracked for hours while troop trains passed carrying thousands of soldiers headed to the front. Eventually, Martha gained passage on an overcrowded ship from Rotterdam to New York, borrowing a small couch in another woman’s cabin.

Back home, the work of sustaining the Schools turned even more arduous. The Berry Schools had come a long way since 1902, growing from a handful of students to 220 boys and 110 girls and from 80 acres to 2,000. But as the war progressed, ever increasing numbers of boys headed off to Europe. The Schools had little money, and supplies were scarce, as most resources were diverted to the massive war effort. Eventually, more than 500 members of the Berry community served in the military, and 11 lost their lives.

With the armistice of 1918 came the promise of a new dawn. Martha was buoyant. In the March 1919 issue of the Southern Highlander, the school’s official publication from 1907 to 1966, she wrote: “Like a soldier taking stock after the smoke has cleared from off the battlefield, I have been looking back over these seventeen years of the existence of the Berry Schools. My dreams have been tested, and some of them found useless; but through it all the dominating idea of service, which was the foundation stone of the School, has grown and developed.”

In the midst of the armistice celebrations, that spirit of service was soon to be tested once more.

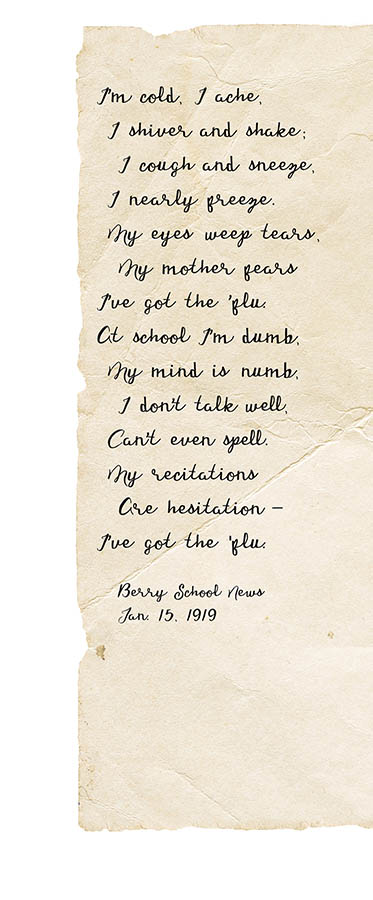

The “Flu” at Berry

As the horrific war was ending, another catastrophe was already underway. By early 1918, the first wave of an H1N1 virus was spreading rapidly in the United States among soldiers mobilized for war. The second and deadliest wave struck from September to November, and a third wave hit in the spring of 1919. While 15-20 million people died as a result of World War I, more than twice that number died worldwide from the 1918 flu pandemic. Global troop movement and overcrowding contributed to the spread of this H1N1 virus. News reporting of the pandemic was initially suppressed by military censors, except for reporting about neutral nations such as Spain. Hence, the misleading label of the “Spanish flu.”

In the same issue of the Southern Highlander that celebrated the end of the war was an article titled “The ‘Flu’ at Berry.” In it, Martha Berry made a plea for funds to build a new infirmary on campus with needed wards for contagious patients. Infectious diseases were a regular occurrence at the beginning of any new school term: mumps, measles and so on. There was no free hospital nearer than Atlanta.

That year, Berry had a perfect storm of influenza, as well as sporadic cases of scarlet fever. Medical care was rudimentary by our standards, with no antibiotics to treat the secondary bacterial infections that can coincide with flu. Nurses were in short supply due to the war.

The two small wards at Berry’s existing infirmary were overflowing with 43 sick boys at one time, leaving no room for social distancing. Female students helped with nursing and made surgical masks. Teachers and workers lived in other parts of the building and had to step over cots in the hallway. One teacher gave up her room to a very sick boy, who developed pneumonia and became Berry’s only student to die in the pandemic.

Pandemic in perspective

Pandemic in perspective

This spring, the COVID-19 virus caught America by surprise. It was another “clap of thunder from a clear sky.” Perhaps we thought that our advanced science and technology would make us immune to a pandemic of this sort. Yet, the virus upended our best-laid plans, dislocated our lives and livelihoods, and shuttered the economy. We would do well to look back at Berry 100 years ago for perspective and a pair of lessons that are as timely now as they were then.

In Martha Berry’s day, people expected hardship. Physical suffering was close at hand as many died at home. More than half of all deaths occurred before the age of 14, and only 8% after age 65. Infectious disease was the leading cause of death. Today, less than 5% of deaths occur before age 14, and almost 70% occur after 65.

When the pandemic arrived at Berry, Martha and her colleagues were determined and pragmatic. Imagine having survived the sufferings and strictures of world war only to be assaulted by a deadlier adversary. Still, the way forward for Martha, the way to respond to hardship, was to embrace it. She and her colleagues understood that life was fragile and worth fighting for. They set about the task of helping the most vulnerable, of walking toward the risks inherent in service that is self-sacrificial and self-giving.

In a similar vein, our nation has recently asked its young people, including many college students, to sacrifice some of life’s special moments, their freedoms, their plans and their incomes to protect the vulnerable members of our communities. Berry seniors missed the opportunity to conclude their final year together. Athletes missed their final season. Research projects were interrupted. Commencement was postponed. For many, the loss has been palpable and not a matter of choice.

Still, Martha would have us understand life’s challenges as being part of a larger whole. This is the first lesson.

Her response to the flu pandemic was not just stoic resolve. She saw her story in the context of a greater story, for she aimed to leave her part of the world better than she found it. Martha’s life was animated by the vision she had for preparing Berry students for meaningful lives of service.

Obligation and opportunity went hand in hand, and it was the “dominating idea of service” – her faith in practice – that gave the greatest joy. She waxed eloquent about this in the 1919 issue of the Southern Highlander quoted earlier: “No potter with his clay, no artist with his colors fresh on the canvas of beauty, no architect with his plans, can equal or surpass in vision what we see when our own boys or girls come to their own.”

Martha also understood hardship and suffering as a necessary instructor for the learning of character. Looking up at one of the massive oaks on campus, she commented: “All the buffeting it has had, all of the knocks. But it is the knocks that have made it grow.” Turning to a student, she added: “The troubles you have had are what make you.”

We want Berry graduates to be resilient, able to withstand setbacks and thrive even in harsh conditions. Although we might wish otherwise, resiliency is forged in moments of loss and suffering. Martha did not shy away from hardship; she leaned into it, recognizing the opportunity for profound growth. That is the second lesson of perspective: “The pursuit of easy things makes us weak. It is the pursuit of the difficult that makes us strong.”

Disruption compels change. It exposes self-satisfaction, lays bare our expectations and challenges our assumptions. It provides the buffeting and knocks that help shape our character. COVID-19 also caused real loss and grief. For many of us, the disruption has offered unfamiliar periods of solitude. What a perfect opportunity to pursue further the joy that comes from being part of a larger story.