Dr. Stephen Briggs

In the 1930s, when the U.S. economy was in tatters, some businessmen asked Martha Berry about the health of the Berry Schools’ investments. Without hesitation, she replied that the investments were doing exceptionally well. After all, her schools were invested 100% in young people as they were the future of our nation’s communities and towns. Her beguiling response emphasized Berry’s mission and unwavering focus on students even if the business of education was dismal.

Martha’s approach to education was akin to “value investing,” a strategy of selecting stocks that are trading in the market for less than their real worth. Martha intentionally sought out students who lacked the economic and social assets needed to fulfill their potential. She invested in young people long before their promise was realized because she was confident that many who had little more to offer than a “sparkle in the eyes” would mature into productive and exemplary citizens.

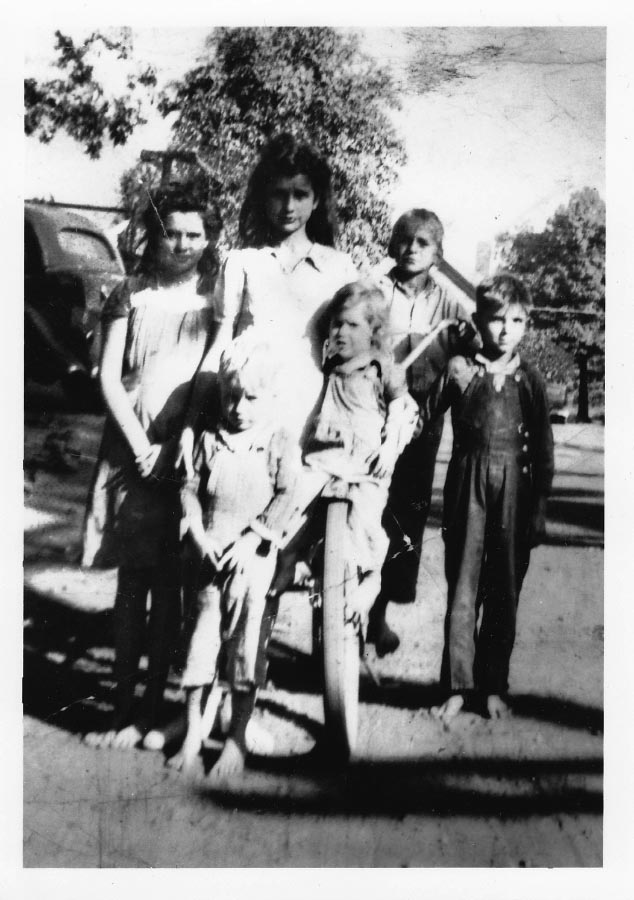

Audrey Bailey was a young woman of this sort. Born in 1930, she entered the world in harsh circumstances at the outset of the Great Depression. She was the fourth of eight children, and her family, like many others, suffered various catastrophes. The Bailey children had to help make ends meet so Audrey began working at a shoe store in Atlanta at age 13. By high school, she was working at Rollfast Bicycles during the day and taking classes at night. She yearned to attend college, but the way forward was unclear, and her chances appeared bleak.

Remarkably, a path opened. At Rollfast, Audrey became good friends with co-worker June Harper, whose parents, Orlin and Mae, elected to take Audrey into their home for a year when Audrey’s family decided to move to another town just before her senior year. Although they had limited financial means, the Harpers believed in the value of education and wanted Audrey to have the same opportunities as their own children. Perhaps they saw a glimpse of her potential. Orlin, through Methodist church connections, arranged for Audrey to receive a work scholarship at Asbury College in Kentucky, where June also attended. Later, the Harpers’ son George went to Berry College. Audrey first visited Berry in 1952 to attend his graduation.

Over the next 50 years, Audrey’s life was full. At Asbury, she met husband Jack Morgan. He finished his engineering degree at Georgia Tech, while she studied business management at Georgia State University. They moved to Detroit and started a family. Then, in 1960, Audrey’s sister Bobbie called to ask if they would come to Atlanta and help her build a business as a remanufacturer of air conditioning and refrigeration compressors. It turned out to be the “call of a lifetime,” the pivotal moment when Audrey’s potential became evident. The business they built, Our-Way, proved highly successful with Bobbie as chief executive officer, Audrey as chief operating officer and Jack as chief engineer. When sold to Carrier in 2001, the operation had 350 employees and annual sales in excess of $45 million.

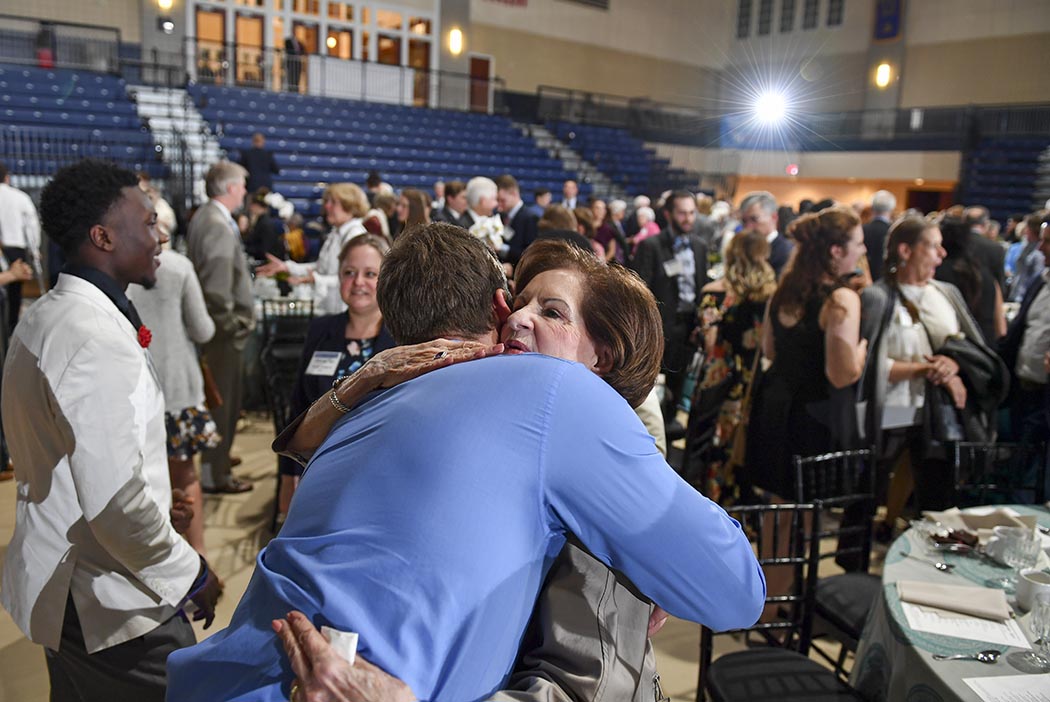

Bobbie and Audrey never forgot their early adversity or humble origins. As successful and pioneering businesswomen, they chose to be committed philanthropists, improving their local community with investments in education, health services, the arts, and children and youth services. Audrey also remembered the Harpers’ pivotal role in her life. In sincere gratitude, she created a scholarship in their honor at Berry in 2001, visiting the campus for only the second time in her life – nearly 50 years after the first.

As Audrey learned more about Berry, she found that its mission and mindset resonated deeply. And so, when the nation experienced the Great Recession of 2007-09, Audrey felt compelled to respond. At a lunch meeting in July 2008, she inquired about innovative ways to help students who had potential and desire but lacked the economic and social capital to attend a school like Berry. She wanted to find a way to make a high-quality education affordable. But based on her own life experience, she also wanted an approach that would build confidence, competence and character. Thus, she was intrigued by a plan that would invest in students who were willing to invest in themselves.

What emerged was a program designed as a partnership of thirds: students supplementing the family contribution (or federal grants) through their own work on campus, with the college and a benefactor each contributing another third to the total cost of education. This idea built on an existing initiative called the Founder’s Program, which had been championed for a number of years by Lt. Col. Reginald Strickland (51C). The intent was to improve and expand on this earlier effort by forming the participants into an intentional community that would provide mentoring and social support across four years. The program would be called Gate of Opportunity because it embodied the spirit of Martha Berry’s original compact with students.

By October of that year, the idea had been studied and vetted, and Audrey endowed the program with an initial gift of $3 million. In Fall 2009, 11 students started the program. Ten years ago, in 2012, the first two Gate of Opportunity students graduated, Kayla Badding and Anna Garber. Today, there are 10 times the original number of Gate students enrolled at Berry.

The Gate program is a treasure. It offers a distinctive solution to a national problem: The goal is for students to graduate in four years without the need for debt. Make no mistake, however, it is a formidable commitment. Students work 45 weeks a year on campus, part-time during regular semesters and full-time during summer and breaks. They pursue a variety of majors and participate actively in campus life, some in the arts and some doing research with faculty. About one-quarter participate in athletics, the same percentage as for other students.

Gate students have full and demanding schedules. They learn to manage their time well. Understandably, they sometimes grow weary and experience doubts, but it is fair to say these moments also instill a tenacity and toughness that sets Gate students apart. They understand firsthand the meaning of sweat equity, the value of investing in oneself, the importance of having a benefactor who has partnered with you, and the value of belonging to a group of like-minded students.

What is the return on this shared investment? Has the program been successful these last 10 years? There are several ways to answer questions of this sort.

To date, 170 Gate participants (85%) have remained in the program to graduation. One-third of these already have gone on to pursue graduate degrees. And although most Gates are recent graduates, they are already achieving (or preparing for) success in a wide variety of careers, such as:

• Attorneys (5)

• Professional musicians (2), professional actor (1), filmmaking specialist (1)

• Medical doctors (5), registered nurses (9), mental or behavioral health professionals (5), other health care professionals (7)

• Veterinarians (7)

• Nonprofit professionals (5), Peace Corps member (1)

• Teachers (12), higher education professionals (3), school counselor (1), coaches (3), athletic department employees (2)

• Ministry professionals (7)

• Project leaders, managers, and marketing, program or communication specialists (34)

• Wealth managers (2), accountants (3)

• Engineers (3), geologist (1), science researchers/Ph.D.s (2)

• Photography business owners (2)

• Technical researchers or professionals (7)

• Professional football player (1), baseball scout (1)

• Police officer (1)

• Published author (1)

This list demonstrates in tangible ways the cascading effects of Audrey’s original gift.

The program began with 11 students. In addition to the 170 Gate graduates, 30 others have participated for a time, most of whom went on to graduate at Berry or other colleges. In addition, there are 118 current students in the program, so Audrey’s initial gift has impacted more than 300 students.

That initial gift also has been multiplied many times by way of other gifts, including additional support from Audrey herself, whose generous gifts to the program now total $4.26 million. The Gate endowment today is valued at more than $30 million. It generates $1.5 million in scholarships annually, and since 2009, $10 million has been distributed to students. In years to come, gifts and pledges will grow the number of students supported annually to 156.

It is reasonable to assess the impact of Audrey’s initial gift in terms of this flourishing endowment and the growing number of scholarships awarded and dollars invested. But her primary interest always has been in the lives and stories of the students themselves. She evaluates success in terms of the promise and potential of Berry students.

Martha Berry began her work believing that the gift of education was the means by which young people could rise up to serve as strong pillars for their families and communities. Audrey’s life is a testimony to Martha’s vision. She became a sturdy pillar. And she embraced with gratitude the gift of opportunity she received from the Harper family, years later returning that gift many times over to students here at Berry.

Like Martha, Audrey’s investments are doing exceptionally well. And like Martha, hers is a legacy of lives.